贝叶斯回归推断算法(Part II)¶

在 Part I 中,我们研究了如何使用SVI在简单的贝叶斯线性回归模型上进行推理。在本教程中,we’ll explore more expressive guides as well as exact inference techniques. 我们将使用与以前相同的数据集。

贝叶斯线性回归:我们的目标是再次根据数据集的两个特征预测一个国家的人均 log GDP - whether the nation is in Africa, and its Terrain Ruggedness Index, but we will explore more expressive guides.

+++++ 学完本文,您将看懂如下代码

[9]:

import logging, os, torch, pyro

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pyro.optim as optim

import pyro.distributions as dist

from torch import nn

from torch.distributions import constraints

from functools import partial

from pyro.nn import PyroModule, PyroSample, Predictive

from pyro.infer import SVI, Trace_ELBO

from pyro.infer.autoguide import AutoDiagonalNormal

pyro.set_rng_seed(1)

assert pyro.__version__.startswith('1.3.0')

%matplotlib inline

plt.style.use('default')

logging.basicConfig(format='%(message)s', level=logging.INFO)

pyro.enable_validation(True)

DATA_URL = "https://d2hg8soec8ck9v.cloudfront.net/datasets/rugged_data.csv"

rugged_data = pd.read_csv(DATA_URL, encoding="ISO-8859-1")

[10]:

def model(is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp):

a = pyro.sample("a", dist.Normal(0., 10.))

b_a = pyro.sample("bA", dist.Normal(0., 1.))

b_r = pyro.sample("bR", dist.Normal(0., 1.))

b_ar = pyro.sample("bAR", dist.Normal(0., 1.))

sigma = pyro.sample("sigma", dist.Uniform(8.0, 10.))

mean = a + b_a * is_cont_africa + b_r * ruggedness + b_ar * is_cont_africa * ruggedness

with pyro.plate("data", len(ruggedness)):

pyro.sample("obs", dist.Normal(mean, sigma), obs=log_gdp)

def guide(is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp):

a_loc = pyro.param('a_loc', torch.tensor(0.))

a_scale = pyro.param('a_scale', torch.tensor(1.), constraint=constraints.positive)

sigma_loc = pyro.param('sigma_loc', torch.tensor(1.), constraint=constraints.positive)

weights_loc = pyro.param('weights_loc', torch.randn(3))

weights_scale = pyro.param('weights_scale', torch.ones(3), constraint=constraints.positive)

a = pyro.sample("a", dist.Normal(a_loc, a_scale))

b_a = pyro.sample("bA", dist.Normal(weights_loc[0], weights_scale[0]))

b_r = pyro.sample("bR", dist.Normal(weights_loc[1], weights_scale[1]))

b_ar = pyro.sample("bAR", dist.Normal(weights_loc[2], weights_scale[2]))

sigma = pyro.sample("sigma", dist.Normal(sigma_loc, torch.tensor(0.05)))

mean = a + b_a * is_cont_africa + b_r * ruggedness + b_ar * is_cont_africa * ruggedness

[11]:

svi = SVI(model, guide, optim.Adam({"lr": .05}),loss=Trace_ELBO())

is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp = train[:, 0], train[:, 1], train[:, 2]

pyro.clear_param_store()

num_iters = 5000 if not smoke_test else 2

for i in range(num_iters):

elbo = svi.step(is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp)

if i % 500 == 0:

logging.info("Elbo loss: {}".format(elbo))

Elbo loss: 5795.467590510845

Elbo loss: 415.8169444799423

Elbo loss: 250.71916329860687

Elbo loss: 247.19457268714905

Elbo loss: 249.2004036307335

Elbo loss: 250.96484470367432

Elbo loss: 249.35092514753342

Elbo loss: 248.7831552028656

Elbo loss: 248.62140649557114

Elbo loss: 250.4274433851242

[13]:

num_samples = 1000

predictive = Predictive(model, guide=guide, num_samples=num_samples)

svi_samples = {k: v.reshape(num_samples).detach().cpu().numpy()

for k, v in predictive(log_gdp, is_cont_africa, ruggedness).items()

if k != "obs"}

for site, values in summary(svi_samples).items():

print("Site: {}".format(site))

print(values, "\n")

Site: a

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 9.177502 0.062302 9.077003 9.134532 9.178522 9.215999 9.278267

Site: bA

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 -1.895068 0.118995 -2.0918 -1.974353 -1.89098 -1.813422 -1.702851

Site: bR

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 -0.157187 0.038121 -0.222267 -0.181703 -0.155021 -0.130235 -0.095558

Site: bAR

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 0.304799 0.066955 0.19294 0.261902 0.304932 0.350269 0.412381

Site: sigma

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 0.902913 0.049275 0.822383 0.870878 0.901005 0.938589 0.983858

Model + Guide¶

We will write out the model again, similar to that in Part I, but explicitly without the use of PyroModule. We will write out each term in the regression, using the same priors. bA and bR are regression coefficients corresponding to is_cont_africa and ruggedness, a is the intercept, and bAR is the correlating factor between the two features.

Writing down a guide will proceed in close analogy to the construction of our model, with the key difference that the guide parameters need to be trainable. To do this we register the guide parameters in the ParamStore using pyro.param(). Note the positive constraints on scale parameters.

[5]:

# Utility function to print latent sites' quantile information.

def summary(samples):

site_stats = {}

for site_name, values in samples.items():

marginal_site = pd.DataFrame(values)

describe = marginal_site.describe(percentiles=[.05, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 0.95]).transpose()

site_stats[site_name] = describe[["mean", "std", "5%", "25%", "50%", "75%", "95%"]]

return site_stats

# Prepare training data

df = rugged_data[["cont_africa", "rugged", "rgdppc_2000"]]

df = df[np.isfinite(df.rgdppc_2000)]

df["rgdppc_2000"] = np.log(df["rgdppc_2000"])

train = torch.tensor(df.values, dtype=torch.float)

SVI¶

As before, we will use SVI to perform inference.

[6]:

from pyro.infer import SVI, Trace_ELBO

svi = SVI(model, guide, optim.Adam({"lr": .05}),loss=Trace_ELBO())

is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp = train[:, 0], train[:, 1], train[:, 2]

pyro.clear_param_store()

num_iters = 5000 if not smoke_test else 2

for i in range(num_iters):

elbo = svi.step(is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp)

if i % 500 == 0:

logging.info("Elbo loss: {}".format(elbo))

Elbo loss: 5795.467590510845

Elbo loss: 415.8169444799423

Elbo loss: 250.71916329860687

Elbo loss: 247.19457268714905

Elbo loss: 249.2004036307335

Elbo loss: 250.96484470367432

Elbo loss: 249.35092514753342

Elbo loss: 248.7831552028656

Elbo loss: 248.62140649557114

Elbo loss: 250.4274433851242

[7]:

from pyro.infer import Predictive

num_samples = 1000

predictive = Predictive(model, guide=guide, num_samples=num_samples)

svi_samples = {k: v.reshape(num_samples).detach().cpu().numpy()

for k, v in predictive(log_gdp, is_cont_africa, ruggedness).items()

if k != "obs"}

Let us observe the posterior distribution over the different latent variables in the model.

[8]:

for site, values in summary(svi_samples).items():

print("Site: {}".format(site))

print(values, "\n")

Site: a

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 9.17702 0.059607 9.07811 9.140463 9.178211 9.217098 9.27152

Site: bA

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 -1.890622 0.122805 -2.08849 -1.979107 -1.887476 -1.803683 -1.700853

Site: bR

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 -0.157847 0.039538 -0.22324 -0.183673 -0.157873 -0.133102 -0.091713

Site: bAR

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 0.304515 0.067683 0.194583 0.259464 0.304907 0.348932 0.415128

Site: sigma

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 0.902898 0.047971 0.824166 0.870317 0.901981 0.935171 0.981577

HMC¶

In contrast to using variational inference which gives us an approximate posterior over our latent variables, we can also do exact inference using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), a class of algorithms that in the limit, allow us to draw unbiased samples from the true posterior. The algorithm that we will be using is called the No-U Turn Sampler (NUTS) [1], which provides an efficient and automated way of running Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. It is slightly slower than variational inference, but provides an exact estimate.

[9]:

from pyro.infer import MCMC, NUTS

nuts_kernel = NUTS(model)

mcmc = MCMC(nuts_kernel, num_samples=1000, warmup_steps=200)

mcmc.run(is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp)

hmc_samples = {k: v.detach().cpu().numpy() for k, v in mcmc.get_samples().items()}

Sample: 100%|██████████| 1200/1200 [00:30, 38.99it/s, step size=2.76e-01, acc. prob=0.934]

[10]:

for site, values in summary(hmc_samples).items():

print("Site: {}".format(site))

print(values, "\n")

Site: a

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 9.182098 0.13545 8.958712 9.095588 9.181347 9.277673 9.402615

Site: bA

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 -1.847651 0.217768 -2.19934 -1.988024 -1.846978 -1.70495 -1.481822

Site: bR

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 -0.183031 0.078067 -0.311403 -0.237077 -0.185945 -0.131043 -0.051233

Site: bAR

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 0.348332 0.127478 0.131907 0.266548 0.34641 0.427984 0.560221

Site: sigma

mean std 5% 25% 50% 75% 95%

0 0.952041 0.052024 0.869388 0.914335 0.949961 0.986266 1.038723

Comparing Posterior Distributions¶

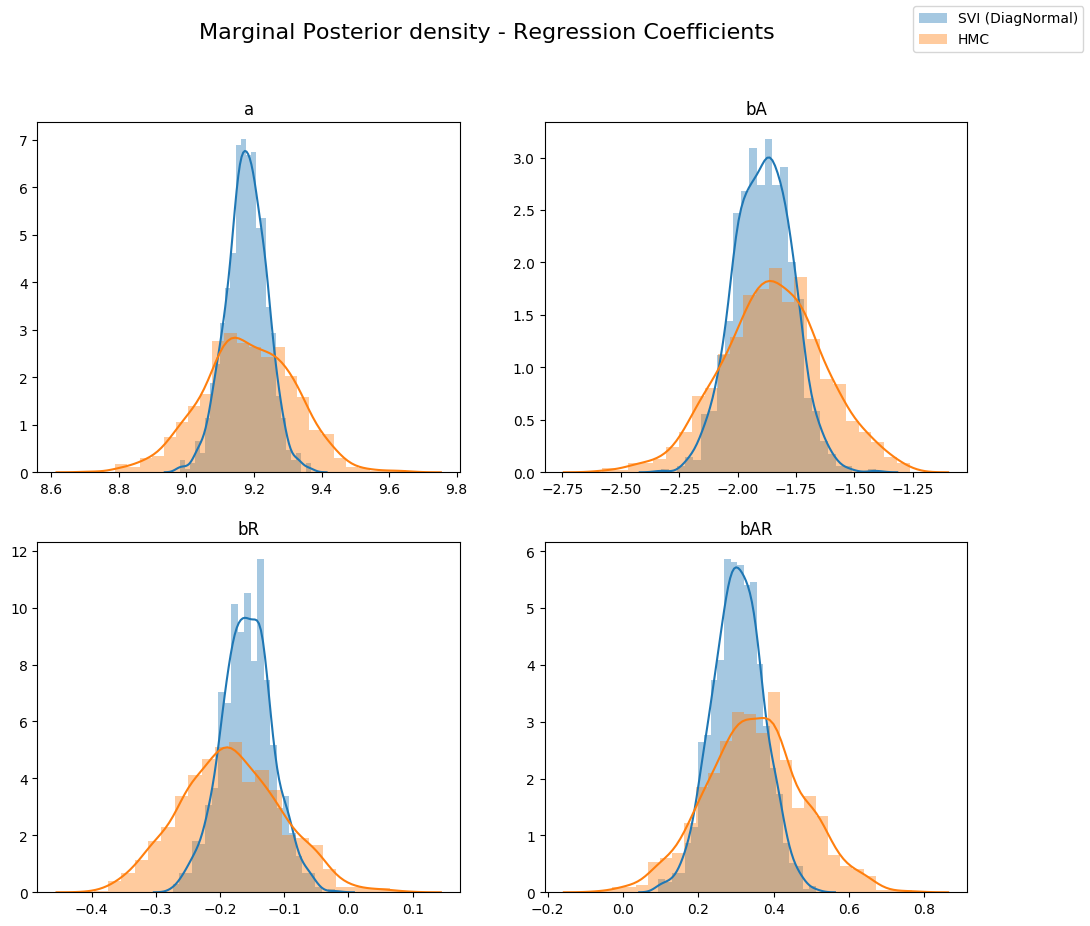

Let us compare the posterior distribution of the latent variables that we obtained from variational inference with those from Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. As can be seen below, for Variational Inference, the marginal distribution of the different regression coefficients is under-dispersed w.r.t. the true posterior (from HMC). This is an artifact of the KL(q||p) loss (the KL divergence of the true posterior from the approximate posterior) that is minimized by Variational Inference.

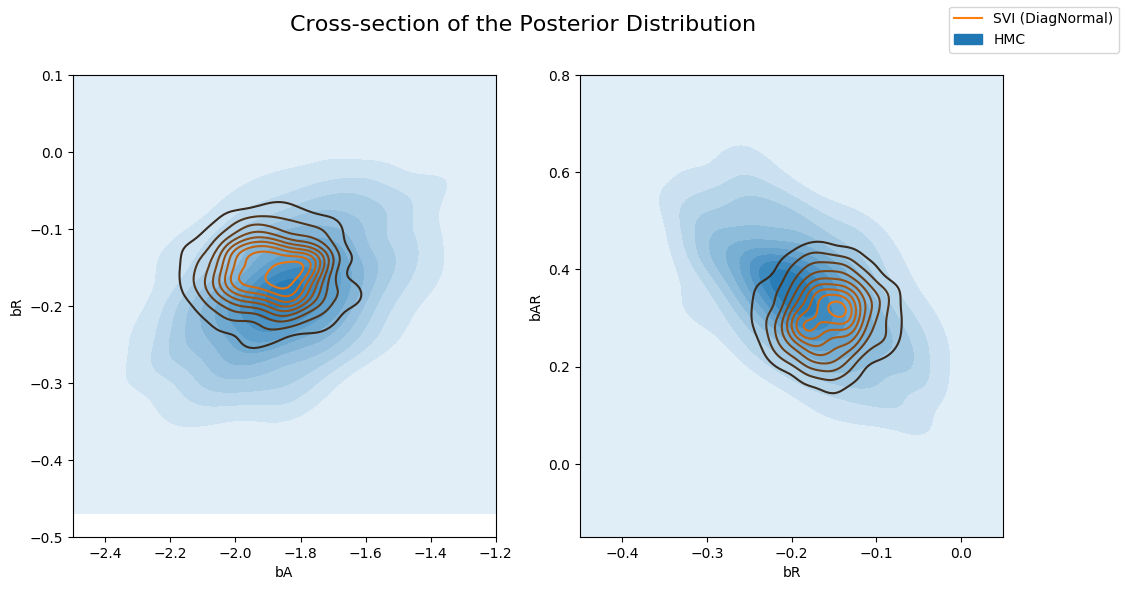

This can be better seen when we plot different cross sections from the joint posterior distribution overlaid with the approximate posterior from variational inference. Note that since our variational family has diagonal covariance, we cannot model any correlation between the latents and the resulting approximation is overconfident (under-dispersed)

[11]:

sites = ["a", "bA", "bR", "bAR", "sigma"]

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=2, figsize=(12, 10))

fig.suptitle("Marginal Posterior density - Regression Coefficients", fontsize=16)

for i, ax in enumerate(axs.reshape(-1)):

site = sites[i]

sns.distplot(svi_samples[site], ax=ax, label="SVI (DiagNormal)")

sns.distplot(hmc_samples[site], ax=ax, label="HMC")

ax.set_title(site)

handles, labels = ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

fig.legend(handles, labels, loc='upper right');

[12]:

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(12, 6))

fig.suptitle("Cross-section of the Posterior Distribution", fontsize=16)

sns.kdeplot(hmc_samples["bA"], hmc_samples["bR"], ax=axs[0], shade=True, label="HMC")

sns.kdeplot(svi_samples["bA"], svi_samples["bR"], ax=axs[0], label="SVI (DiagNormal)")

axs[0].set(xlabel="bA", ylabel="bR", xlim=(-2.5, -1.2), ylim=(-0.5, 0.1))

sns.kdeplot(hmc_samples["bR"], hmc_samples["bAR"], ax=axs[1], shade=True, label="HMC")

sns.kdeplot(svi_samples["bR"], svi_samples["bAR"], ax=axs[1], label="SVI (DiagNormal)")

axs[1].set(xlabel="bR", ylabel="bAR", xlim=(-0.45, 0.05), ylim=(-0.15, 0.8))

handles, labels = axs[1].get_legend_handles_labels()

fig.legend(handles, labels, loc='upper right');

MultivariateNormal Guide¶

As comparison to the previously obtained results from Diagonal Normal guide, we will now use a guide that generates samples from a Cholesky factorization of a multivariate normal distribution. This allows us to capture the correlations between the latent variables via a covariance matrix. If we wrote this manually, we would need to combine all the latent variables so we could sample a Multivarite Normal jointly.

[13]:

from pyro.infer.autoguide import AutoMultivariateNormal, init_to_mean

guide = AutoMultivariateNormal(model, init_loc_fn=init_to_mean)

svi = SVI(model,

guide,

optim.Adam({"lr": .01}),

loss=Trace_ELBO())

is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp = train[:, 0], train[:, 1], train[:, 2]

pyro.clear_param_store()

for i in range(num_iters):

elbo = svi.step(is_cont_africa, ruggedness, log_gdp)

if i % 500 == 0:

logging.info("Elbo loss: {}".format(elbo))

Elbo loss: 703.0100790262222

Elbo loss: 444.6930855512619

Elbo loss: 258.20718491077423

Elbo loss: 249.05364602804184

Elbo loss: 247.2170884013176

Elbo loss: 247.28261297941208

Elbo loss: 246.61236548423767

Elbo loss: 249.86004841327667

Elbo loss: 249.1157277226448

Elbo loss: 249.86634194850922

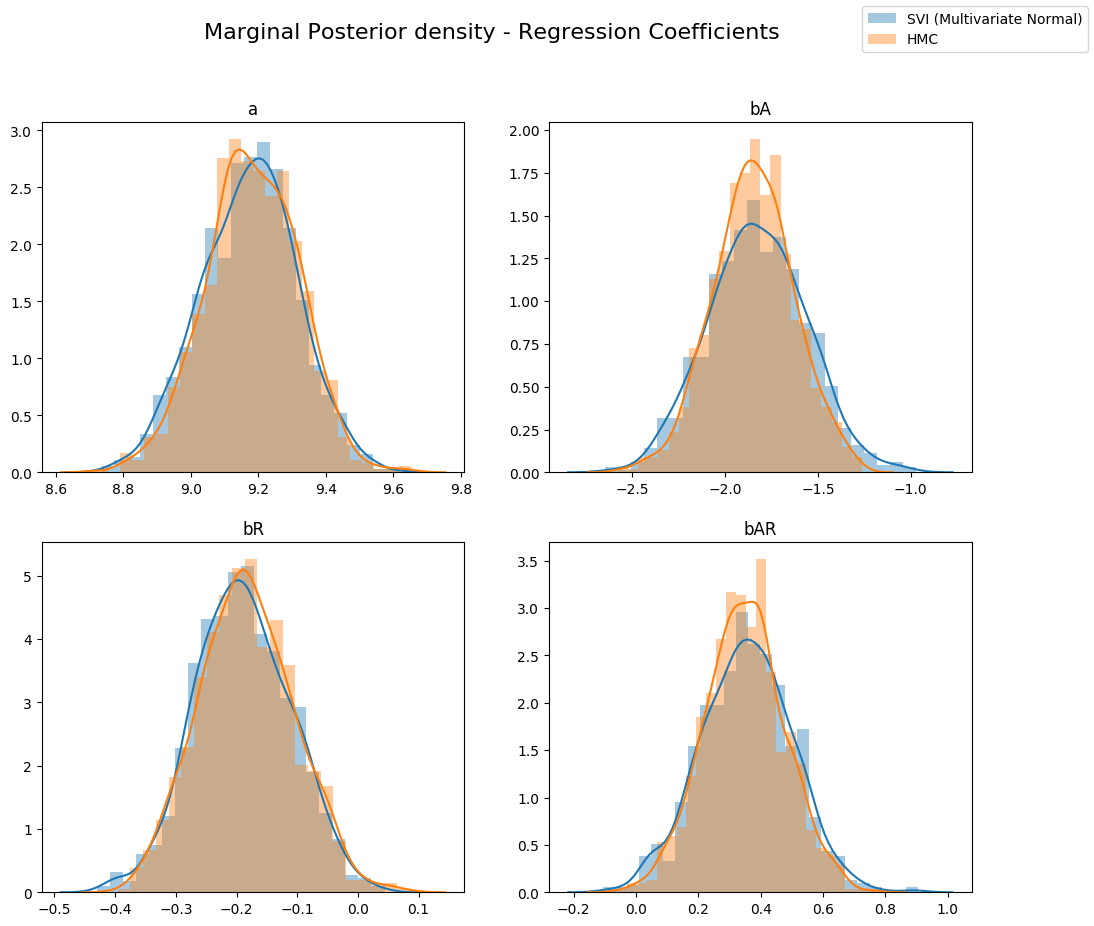

Let’s look at the shape of the posteriors again. You can see the multivariate guide is able to capture more of the true posterior.

[14]:

predictive = Predictive(model, guide=guide, num_samples=num_samples)

svi_mvn_samples = {k: v.reshape(num_samples).detach().cpu().numpy()

for k, v in predictive(log_gdp, is_cont_africa, ruggedness).items()

if k != "obs"}

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=2, figsize=(12, 10))

fig.suptitle("Marginal Posterior density - Regression Coefficients", fontsize=16)

for i, ax in enumerate(axs.reshape(-1)):

site = sites[i]

sns.distplot(svi_mvn_samples[site], ax=ax, label="SVI (Multivariate Normal)")

sns.distplot(hmc_samples[site], ax=ax, label="HMC")

ax.set_title(site)

handles, labels = ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

fig.legend(handles, labels, loc='upper right');

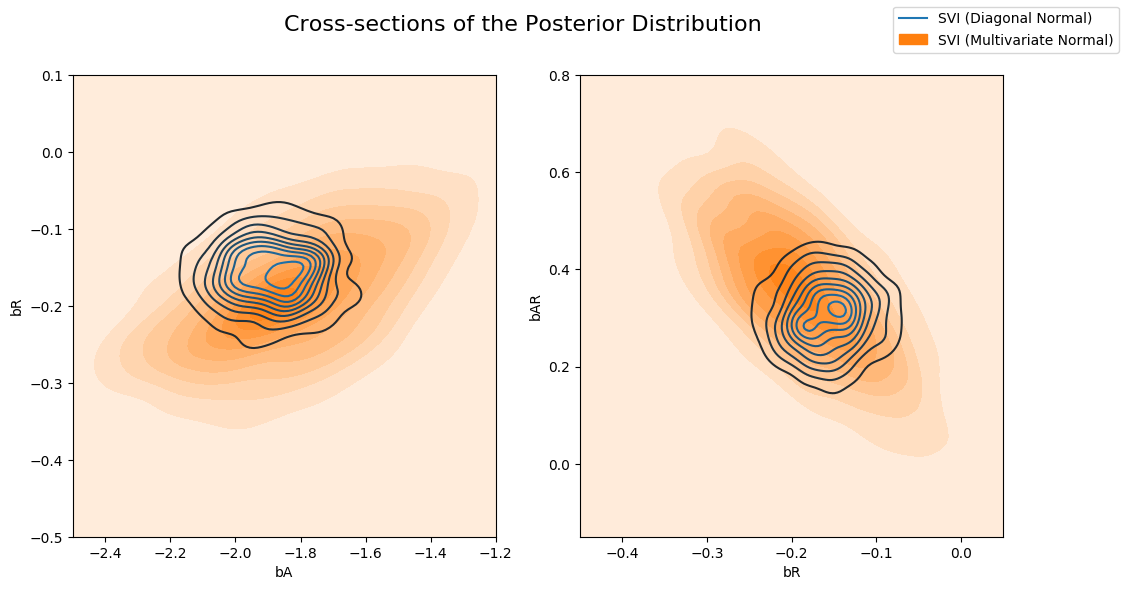

Now let’s compare the posterior computed by the Diagonal Normal guide vs the Multivariate Normal guide. Note that the multivariate distribution is more dispresed than the Diagonal Normal.

[15]:

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(12, 6))

fig.suptitle("Cross-sections of the Posterior Distribution", fontsize=16)

sns.kdeplot(svi_samples["bA"], svi_samples["bR"], ax=axs[0], label="HMC")

sns.kdeplot(svi_mvn_samples["bA"], svi_mvn_samples["bR"], ax=axs[0], shade=True, label="SVI (Multivariate Normal)")

axs[0].set(xlabel="bA", ylabel="bR", xlim=(-2.5, -1.2), ylim=(-0.5, 0.1))

sns.kdeplot(svi_samples["bR"], svi_samples["bAR"], ax=axs[1], label="SVI (Diagonal Normal)")

sns.kdeplot(svi_mvn_samples["bR"], svi_mvn_samples["bAR"], ax=axs[1], shade=True, label="SVI (Multivariate Normal)")

axs[1].set(xlabel="bR", ylabel="bAR", xlim=(-0.45, 0.05), ylim=(-0.15, 0.8))

handles, labels = axs[1].get_legend_handles_labels()

fig.legend(handles, labels, loc='upper right');

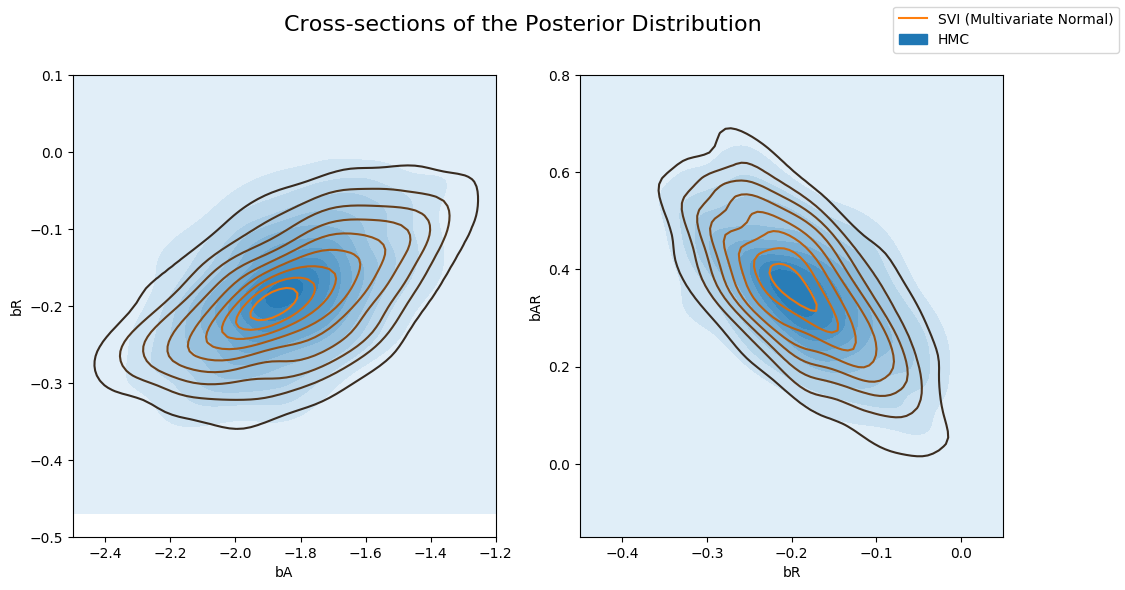

and the Multivariate guide with the posterior computed by HMC. Note that the Multivariate guide better captures the true posterior.

[16]:

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(12, 6))

fig.suptitle("Cross-sections of the Posterior Distribution", fontsize=16)

sns.kdeplot(hmc_samples["bA"], hmc_samples["bR"], ax=axs[0], shade=True, label="HMC")

sns.kdeplot(svi_mvn_samples["bA"], svi_mvn_samples["bR"], ax=axs[0], label="SVI (Multivariate Normal)")

axs[0].set(xlabel="bA", ylabel="bR", xlim=(-2.5, -1.2), ylim=(-0.5, 0.1))

sns.kdeplot(hmc_samples["bR"], hmc_samples["bAR"], ax=axs[1], shade=True, label="HMC")

sns.kdeplot(svi_mvn_samples["bR"], svi_mvn_samples["bAR"], ax=axs[1], label="SVI (Multivariate Normal)")

axs[1].set(xlabel="bR", ylabel="bAR", xlim=(-0.45, 0.05), ylim=(-0.15, 0.8))

handles, labels = axs[1].get_legend_handles_labels()

fig.legend(handles, labels, loc='upper right');

参考文献¶

[1] Hoffman, Matthew D., and Andrew Gelman. “The No-U-turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 15.1 (2014): 1593-1623. https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.4246.