Part I: 仰望天空¶

本文这里对每个章节的引言做一个 summary 来把控全书的框架, 从一个仰望天空的故事讲讲因果推理中的基本概念.

书的网址: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/miguel-hernan/causal-inference-book/

我们总是希望最快的了解相关概念,对教材内容有一个整体的把握。

ch1-ch5 是关于仰望天空和心脏移植的故事。

Ch1-Ch2 因果理论基础概念¶

主要涉及的概念有:

Causal effect

随机试验

Ch1: A definition of causal effect

As a human being, you have already mastered the fundamental concepts of causal inference. You certainly know what a causal effect is; you clearly understand the difference between association and causation; and you have used this knowledge constantly throughout your life. 因果推断工具就像 your liver, you use it everyday without noticing you’re using it. 第一章的目的是 to precisely define causal concepts.

Ch2: Randomized experiments

经典问题:你在街道上看着天空会引起行人也看天空吗?你会说,很简单啊,“I can stand on the sidewalk and flip a coin whenever someone approaches. If heads, I’ll look up; if tails, I’ll look straight ahead. I’ll repeat the experiment a few thousand times. If the proportion of pedestrians who looked up within 10 seconds after I did is greater than the proportion of pedestrians who looked up when I didn’t, I will conclude that my looking up has a causal effect on other people’s looking up.

Your solution to our challenge was to conduct a randomized experiment. It was an experiment because the investigator (you) carried out the action of interest (looking up), and it was randomized because the decision to act on any study subject (pedestrian) was made by a random device (coin flipping). Not all experiments are randomized. For example, you could have looked up when a man approached and looked straight ahead when a woman did. Then the assignment of the action would have followed a deterministic rule (up for man, straight for woman) rather than a random mechanism. If your action had been determined by the pedestrian’s sex, critics could argue that the “looking up” behavior of men and women differs (women may look up less often than do men after you look up) and thus your study compared essentially “noncomparable” groups of people. This chapter describes why randomization results in convincing causal inferences. 本章就是在说明有了随机化试验,我们可以做因果推断。

Ch2 的简单理解

这一章节的内容理解要专注于一个公式:

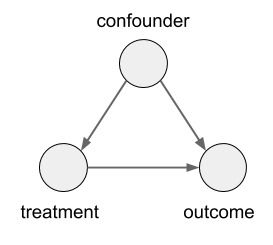

\(L, T, Y\) 分别是 confounder, treatment, outcome.

因果效应本质就是要考察 \(do(T)\) 对 \(Y\) 的影响。

因果效应总是针对于于特定的总体的,离开了总体根本不能谈因果效应。

In clinical research, randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for demonstrating the efficacy and safety of a new treatment. Causal effect 难以估计的根本原因是 missing values for individual counterfatural outcome. 随机化控制试验是保证 missing values occured by chance, which means there is no difference w.r.t causal effects between treated and untreated groups.

Ch3-Ch5 观测研究,effect modify 和 interaction¶

effect modification 考虑是推断目标变成了某个子总体上的因果效应。而 interaction 考虑的是多个治疗之间的交互,目标是找到最最大因果效应的干预。

Ch3: Observational studies

回顾经典问题, 你在街道上看着天空会引起行人也看天空吗?你做随机化试验的时候老师抬头仰望天空,从而导致脖子疼。所以呀,你决定转向另外一种回答这个问题的方法: Find a nearby pedestrian who is standing in a corner and not looking up. Then find a second pedestrian who is walking towards the first one and not looking up either. Observe and record their behavior during the next 10 seconds. Observe and record their behavior during the next 10 seconds. Repeat this process a few thousand times. You could now compare the proportion of second pedestrians who looked up after the first pedestrian did, and compare it with the proportion of second pedestrians who looked up before the first pedestrian did. Such a scientific study in which the investigator observes and records the relevant data is referred to as an observational study(观察研究的定义).

If you had conducted the observational study described above, critics could argue that two pedestrians may both look up not because the first pedestrian’s looking up causes the other’s looking up, but because they both heard a thunderous noise above or some rain drops started to fall, and thus your study findings are inconclusive as to whether one’s looking up makes others look up. These criticisms do not apply to randomized experiments, which is one of the reasons why randomized experiments are central to the theory of causal inference. However, in practice, the importance of randomized experiments for the estimation of causal effects is more limited. Many scientific studies are not experiments. Much human knowledge is derived from observational studies. Think of evolution, tectonic plates, global warming, or astrophysics. Think of how humans learned that hot coffee may cause burns.

观察研究会有 confounding 的问题,随机试验能解决这个问题,但是随机试验由于各种因素很难进行,我们只拥有观察数据,我们依然需要做因果推断,那么如何解决这个矛盾呢?

This chapter reviews some conditions under which observational studies lead to valid causal inferences. 可以将观察性研究视作条件随机实验的三个条件下是:

the values of treatment under comparison correspond to well-defined interventions that, in turn, correspond to the versions of treatment in the data

the conditional probability of receiving every value of treatment, though not decided by the investigators, depends only on the measured covariates

the conditional probability of receiving every value of treatment is greater than zero, i.e., positive

Ch4: Effect modification

我们用一个例子说明其概念。在心脏移植治疗中涉及到三个变量 \(L\) ,\(A\), \(Y\) 分别是情况是否紧急,是否接受心脏移植和是否存活。是否接受心脏移植手术和情况是否紧急是强相关的,并且病人能否存活也与 \(L\) 强相关,我们称 the effect of treatment is modified by :math:`L`, or there is effect modification by L。

到目前为止,我们关注总体的是平均因果效应。 However, many causal questions are about subsets of the population. 继续考虑因果问题“抬头仰望天空是否也会使其他行人抬头吗?”您可能有兴趣分别计算城市居民和游客对治疗的平均因果效应(即仰望天空),而不是计算整个行人总体的平均因果效应。

The decision whether to compute average effects in the entire population or in a subset 取决与你的推断目标. 在某些情况下,您可能并不关心不同总体之间的效果差异。 For example, suppose you are a policy maker considering the possibility of implementing a nationwide water fluoridation program. Because this public health intervention will reach all households in the population, 所以您的主要兴趣是整个人口中的平均因果效应,而不是特定的子集。 You will be interested in characterizing how the causal effect varies across subsets of the population when the intervention can be targeted to different subsets, or when the findings of the study need to be applied to other populations.

Ch5: Interaction

继续考虑一项随机实验,以回答因果问题“抬头仰望天空是否也会使其他行人抬头吗?”到目前为止,我们的兴趣仅限于 a single treatment (looking up) 对整个人群或其中一部分的因果效用。但是,许多因果问题实际上是关于两种或多种同时治疗的效果。例如,假设除了随机分配您的 looking up 之外,我们还随机分配您是穿着衣服还是赤身裸体站在街道上。现在,我们可以提出类似的问题:如果穿好衣服,looking up 的因果效应是多少?如果你是赤裸裸的呢?如果这两种因果效应不同,我们就说正在考虑的treatments (looking up and being dressed) interact in bringing about the outcome.

When joint interventions on two or more treatments are feasible, the identification of interaction allows one to 实现最有效的干预. Thus understanding the concept of interaction is key for causal inference.

本章在我们已经熟悉的反事实框架内和在 sufficient-component-cause 框架内,提供了 interaction between two treatments 相互作用的正式定义。

因果图模型可以把任意多个控制变量控制成任何值。

Ch6 因果图模型¶

前面我们通过一个仰望天空和心脏移植的简单故事讲解清楚了因果模型的基本概念,现在我们介绍更加强大的模型处理更加复杂的因果推断。

The goal was to provide a gentle introduction to the ideas underlying the more sophisticated approaches that are required in realistic settings. Because the scenarios we considered were so simple, there was really no need to make the causal network explicit. As we start to turn our attention towards more complex situations, however, it will become crucial to be explicit about what we know and what we assume about the variables relevant to our particular causal inference problem.

This chapter introduces a graphical tool to represent our qualitative expert knowledge and a priori assumptions about the causal structure of interest. By summarizing knowledge and assumptions in an intuitive way, graphs help clarify conceptual problems and enhance communication among investigators. The use of graphs in causal inference problems makes it easier to follow a sensible advice: draw your assumptions before your conclusions.

主要的图模型是 Causal directed acyclic graphs. Richardson and Robins(2013) devoped the Single World Intervention Graph

Ch7: 混杂因子¶

Suppose an investigator conducted an observational study to answer the causal question “does one’s looking up to the sky make other pedestrians look up too?” She found an association between a first pedestrian’s looking up and a second one’s looking up. However, she also found that pedestrians tend to look up when they hear a thunderous noise above. Thus it was unclear what was making the second pedestrian look up, the first pedestrian’s looking up or the thunderous noise? She concluded the effect of one’s looking up was confounded by the presence of a thunderous noise. 也就是说结果 \(Y\) 有可能并不是你的 Action \(A\) 引起的,而是由雷声 \(L\) 引起的。

In randomized experiments treatment is assigned by the flip of a coin, but in observational studies treatment (e.g., a person’s looking up) may be determined by many factors (e.g., a thunderous noise). If those factors affect, (Obervational study 中的 outcome 可能被很多其他因素影响,并不是随机试验,需要条件才能看作是随机试验) the risk of developing the outcome (e.g., another person’s looking up), then the effects of those factors become entangled with the effect of treatment. We then say that there is confounding, which is just a form of lack of exchangeability between the treated and the untreated. Confounding is often viewed as the main shortcoming of observational studies. In the presence of confounding, the old adage “association is not causation” holds even if the study population is arbitrarily large. This chapter provides a definition of confounding and reviews the methods to adjust for it.

在 Observational study 中,消除 confounding 的影响和计算因果效应是两个主要问题, Causal effects can be identifiable 的条件是:

没有 common causes of treatment and outcome

或者有 common causes, 但是 engough measured variables to block all backdoor paths

传统上 Confounder 有一个三个条件的定义,和 correlated with \(A\) and \(Y\) and not in the causal paths from \(A\rightarrow Y\). 现在我们对 confouder 的定义有了更准确的认知,控制某个变量,即生一个孩子能够导致独立的变量之间相互联系,也就是说父母变量之间是相关的。

Confounder 就是导致 \(P(Y=y|do(X=x)) \neq P(Y=y|X=x)\) 的原因。

Ch8 选择偏差¶

Suppose an investigator conducted a randomized experiment to answer the causal question “does one’s looking up to the sky make other pedestrians look up too?” She found a strong association between her looking up and other pedestrians’ looking up. Does this association reflect a causal effect? Well, by definition of randomized experiment, confounding bias is not expected in this study. However, there was another potential problem: The analysis included only those pedestrians that, after having been part of the experiment, gave consent for their data to be used(也就是说有些人害羞,不允许你用他的数据进行分析). Shy pedestrians (those less likely to look up anyway) and pedestrians in front of whom the investigator looked up (who felt tricked) were less likely to participate. Thus participating individuals in front of whom the investigator looked up (感觉被戏弄了导致拒绝参与,a reason to decline participation,或者说他发现了你在做试验,然后故意拒绝参与) are less likely to be shy (an additional reason to decline participation) and therefore more likely to lookup. That is, the process of selection of individuals into the analysis guarantees that one’s looking up is associated with other pedestrians’ looking up, regardless of whether one’s looking up actually makes others look up.

An association created as a result of the process by which individuals are selected into the analysis is referred to as selection bias. Unlike confounding, this type of bias is not due to the presence of common causes of treatment and outcome, and can arise in both randomized experiments and observational studies. Like confounding, selection bias is just a form of lack of exchangeability between the treated and the untreated.

This chapter provides a definition of selection bias and reviews the methods to adjust for it.

Selection bias is bias due to the mechanism by which individuals are selected into the analysis. Censoring 数据分析因果效应的时候可能会导致选择偏差,一种思路是把 Censoring 也当成一种 treatment. (missing data 是 selection bias)。因此因果模型给出了一个解决 selection bias and confounding 的方案。

Ch9 测量误差¶

Suppose an investigator conducted a randomized experiment to answer the causal question “does one’s looking up to the sky make other pedestrians look up too?” She found a weak association between her looking up and other pedestrians’ looking up. Does this weak association reflect a weak causal effect? By definition of randomized experiment, confounding bias is not expected in this study. In addition, no selection bias was expected because all pedestrians’ responses–whether they did or did not look up–were recorded. However, there was another problem: the investigator’s collaborator who was in charge of recording the pedestrians’ responses made many mistakes(仰望天空记录数据出了问题怎么办呢?). Specifically, the collaborator missed half of the instances in which a pedestrian looked up and recorded these responses as “did not look up.” Thus, even if the treatment (the investigator’s looking up) truly had a strong effect on the outcome (other people’s looking up), the misclassification of the outcome will result in a dilution of the association between treatment and the (mismeasured) outcome.

We say that there is measurement bias when the association between treatment and outcome is weakened or strengthened as a result of the process by which the study data are measured. 由于在任何研究设计(包括随机实验和观察性研究)下都可能发生测量误差,因此在解释效果评估时始终需要考虑测量偏差。

本章介绍了由于测量误差引起的偏差。仰望天空记录数据出了问题怎么办呢?我们改变图结构, 引入一个带误差的节点.

Intention-to-treat effect: the effect of a misclassified treatment. Why would one be interested in the effect of assigned treatment \(Z\) rather than in the effect of the treatment truly received \(A\)? 下一节将提供此问题的一些答案

In randomized experiments, the per-protocol effect is the causal effect of treatment that would have been observed if all individuals had adhered to their assigned treatment as specified in the protocol of the experiment.

Some authors refer to the per-protocol effect the treatment’s “efficacy,” and to the intention-to-treat effect as the treatment’s “effectiveness.”

Ch10 Random variability¶

假设研究人员进行了一项随机实验,以回答因果问题“抬头仰望天空也会使其他行人抬头吗?”她发现自己的抬头与其他行人的抬头之间存在关联。这种联系是否反映了因果关系? By definition of randomized experiment, confounding bias is not expected in this study. In addition, no selection bias was expected because all pedestrians’ responses–whether they did or did not look up–were recorded, and no measurement bias was expected because all variables were perfectly measured (也就是无系统偏差). 但是,还有另一个问题: the study included only 4 pedestrians, 2 in each treatment group. By chance, 1 of the 2 pedestrians in the “looking up” group, and neither of the 2 pedestrians in the “looking straight” group, was blind. Thus, even if the treatment (the investigator’s looking up) truly had a strong average effect on the outcome (other people’s looking up), half of the individuals in the treatment group happened to be immune to the treatment. The small size of the study population led to a dilution of the estimated effect of treatment on the outcome.

There are two qualitatively different reasons why causal inferences may be wrong: - systematic bias and - random variability.

The previous three chapters described three types of systematic biases: selection bias, measurement bias–both of which may arise in observational studies and in randomized experiments–and unmeasured confounding–which is not expected in randomized experiments. So far we have disregarded the possibility of bias due to random variability by restricting our discussion to huge study populations. 也就是说, we have operated as if the only obstacles to identify the causal effect were confounding, selection, and measurement. 那么是时候回到现实来了: the size of study populations in etiologic(病因) research rarely precludes the possibility of bias due to random variability.

This chapter discusses random variability and how we deal with it.

到底怎么处理呢? 用的 minimal num of samples to cover the true parameter with prob 0.95 相关的方法, 也有考察样本数的增加,精度的增加的数量级问题.

(统计学家如何定义 identification 问题)By acting as if we could obtain an unlimited number of individuals for our studies, we could ignore random fluctuations and could focus our attention on systematic biases due to confounding, selection, and measurement. Statisticians have a name for problems in which we can assume the size of the study population is effectively infinite: identification problems.

每个 causal quantity 都对应一个 identification 的问题。 - These so-called identifying conditions were exchangeability, positivity, and consistency. - the estimand(预估量是 Causal quantity 对应的 identification 版本,也就是说无限样本情况下需要估计的参数). An estimator is a rule that takes the data from any sample from the super-population and produces a numerical value for the estimand. 也就是说 An estimator is consistent for a particular estimand if the estimates get (arbitrarily) closer to the parameter as the sample size increases

有了这些概念之后,我们讲清楚 random variability 导致的 wrong causal inference 是什么样子了。i.e. Even consistent estimators may result in point estimates that are far from the super-population value.

(样本量不够会导致 the point estimate and the super-population value 之间的大偏差)Large differences between the point estimate and the super-population value of a proportion are much more likely to happen when the size of the study population is small compared with that of the super-population.

(统计理论可以让我们有置信区间) statistical theory allows one to quantify this confidence in the form of a confidence interval around the point estimate.

there are two sources of randomness: sampling variability and nondeterministic counterfactuals.